The remains of Cymer Abbey today: in typical Cistercian fashion, it stands in an isolated location in a secluded valley.

During our recent vacation in Wales, we managed to spend some time at Cymer Abbey, near the ancient village of Llanelltyd, and just northwest of Dolgellau. The name of the place can be spelt variously as Cymer or Cymmer, but in the interests of consistency, we will write of it here as Cymer.

The Cistercian abbey of St. Mary at Cymer was never a large or wealthy house, but it did have a long history.

In fact, the General Chapter at Citeaux received requests to build an abbey for the order, in both 1198 and 1199 AD, from a local prince of North Wales; a leader described as 'Grifin'.

Two extant versions of the ancient Brut y Tywysogion, (the Chronicle of the Welsh Princes), report the foundation of Cymer Abbey: the first speaks of a community coming there from Cwmhir Abbey; the second version suggests that it was the community from Cwmhir. Historians speculate that this may suggest that political instability led to the temporary removal of the entire Cwmhir community to Cymer.

In any case, although no foundation charter survives for Cymer, there is an extant confirmation charter of Llywelyn ab lorwerth; a cousin of the founder. In 1209, this affirmed the original endowment made by Gruffud ap Cynan, Lord of Meirionydd.

I love how that sounds like someone straight out of Tolkien's, Lord of the Rings!

Cymer was established on the eastern bank of the River Mawddach, near to its confluence with the River Wnion. Appropriately enough then, 'Cymer' means 'meeting of the waters'. I know I've already used this next picture recently, but it is so evocative of the peace of the place, that I thought it worthwhile including again. You could stand there and drink it in all day, really!

As I've said before, the present bridge is thought to date to the second quarter of the 18th-Century. However, records prove that there was a much earlier bridge near the site as early as the 1400's.

There are many places in the the UK and beyond in Europe, where local monasteries constructed and maintained bridges to facilitate local travel and commerce. This civilizing tendency was expressive of monastic charity to locals and travellers, as well as a useful source of income for the monastic community.

Cymer's proximity to these rivers gave the original monks fishing rights and access to the Irish Sea; thus facilitating communications with other monasteries and with the international trade in wool. As the Cistercians were expert sheep farmers, Cymer's location had much to recommend it.

In his expert study, Architecture of Solitude - Cistercian Abbeys in 12th-Century England, Peter Fergusson describes how local patrons gained both spiritual and temporal benefits from the endowment of a Cistercian monastery. Although his book deals with the situation in England, there are sufficient commonalities with that in Wales at the same time. And so, the primary benefit to a local patron, English or Welsh, would have been the Masses and prayers offered in perpetuity for the salvation of their souls, for those of their descendants and for their temporal welfare.

In that second instance, the endowment of a Cistercian monastery - something which was often cheaper to accomplish than those of other orders due to their insistence on poverty, simplicity and preferred choice of settlements in isolated valleys - would also bring local feudal lords access to new farming techniques and, importantly, an opening to the great sources of power in both Rome and Citeaux. In a place like Wales, with troubles from Kings of England, that could be a particularly helpful benefit at certain times.

If you are at all interested in Cistercian history, an author worth consulting is Janet Burton, Professor of Medieval History at Trinity, St. David at Lampeter, in Wales. Her book, The Cistercians in the Middle Ages - which was co-written with Julie Kerr and forms part of a series of books by various authors on the major religious orders in those times - provides an interesting, scholarly and largely sympathetic treatment of Cistercian history. I have also found Prof. Janet Burton's other text, a scholarly guide and comprehensive gazetteer called Abbeys and Priories of Medieval Wales, (this time co-written with Karen Stober of the University of Lleida, Catalunya), to be an absolutely invaluable resource during sojourns into Wales.

Professors Burton and Stober speculate that Cymer's proximity to the coast, combined with the aforementioned and typical closeness to the local feudal lord, may actually have brought not only commerical benefits to Cymer, but also political troubles.

As we've already established, Cymer was never a large or wealthy house, and it certainly looks to have suffered during times of social upheaval and war.

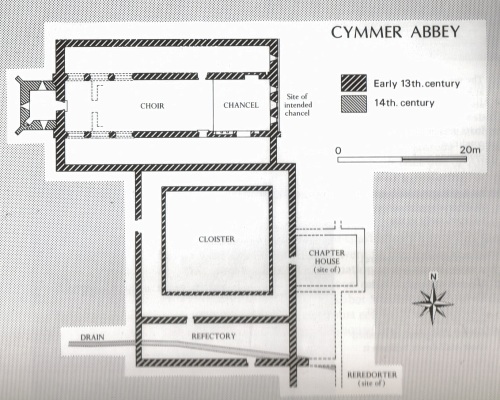

The plan of Cymer (depicted here with the alternative spelling of Cymmer) as it would have been when built. The community's poverty and paucity of numbers seem to have precluded the construction of the originally intended, and much more typically Cistercian, cruciform church. It is even possible that the West range of the claustral complex was never constructed either. Note the unusual tower at the west end of the church; and then see its remains in the second photograph below.

One of the more unhappy themes which crops up frequently in the histories of a number of the Welsh monasteries, most especially those closer to the disputed border with England, is the fact of damage and destruction being visited on them by opposing solidiers, or even just mobs of opposing feudal lords during periods of instability.

In 1241, still fairly early in Cymer's initial decades of growth, King Henry III's troops inflicted damage on the monastic buildings at Cymer. It seems amazing to modern ears to hear of Christian kings, often having founded monastic settlements of their own, permitting such evil acts. Such is the state of fallen human nature! More positively, the chronicles and records show kings at times making financial donations and gifts of reparation to monasteries in the years following such terrible attacks.

The records of the General Chapter at Citeaux report that, during the very year of the damage done by King Henry III's men to Cymer, the Cistercian leaders were so concerned at the reduced state of the place, that they considered dispersing Cymer's monks.

In the event, this does not appear to have been resorted to. However, in 1274, Abbot Llywelyn was finding himself too financially hard pressed to attend that year's General Chapter, until he was loaned some funds by Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, the latest in the line of Lords of Meirionydd.

There's that splendid Lord of the Rings sound again!

Lord Llywelyn actually made Cymer his base of operations in 1275, and again in 1279. However, it was the English King who made his regal headquarters there, during his Welsh campaigns, in 1283!

For all its troubles, the abbey was compensated with the sum of £80. However, when Pope Nicholas IV's Taxatio ecclesiastica, made its official enquiry into the taxable assets of all religious houses in 1291, Cymer's income was valued at just over £23.

The claustral ranges are no longer extant at Cymer, however their plan remains helpfully marked out in stone. This view looks towards the church from the south-western corner of the cloister complex. In the black and white plan image further above, that would be situated in the bottom left hand corner of the cloister square.

By 1379, just four monks were still trying to live the Cistercian life at Cymer. I say ''trying to'' as it would have been difficult for such a low number to maintain the daily monastic horarium and to run the buildings and land. Cistercian statutes from the era called for a community of twelve men with a prior and additional lay brothers. Later, in the mid-15th-Century, the income at Cymer fell so low that the monastery needed to be taken into royal custody a couple of times.

As the caption to the plan image of the monastery's buildings mentions above, this paucity of members and poverty of income caused Cymer's original building plans to be somewhat curtailed.

Colin Platt, a thorough historian of the Middle Ages, and former chair of Medieval History at Southampton University, notes that the wars in Wales caused Cymer to lack both the originally intended, and far more typically Cistercian, presbytery and crossing of what, would then have been, a cruciform church. Indeed, unable to complete their building on the model of many larger Cistercian houses of the period, Cymer's community had to worship in the lay brethrens' choir; this was more normally a separate area.

It also seems probable that the construction of the west claustral range, the usual preserve of the lay brethren, was omitted altogether. In larger houses, it was the lay brethren who not only occupied the west claustral ranges and western end of the nave of the cruciform churches, but who also carried out the bulk of the manual and agricultural labour. This was one aspect which had made the Cistercians such a driving force in monastic growth and reform in these lands.

As our pictures show, in spite of the cruel Henrician depradations of the 16th-Century, and the centuries of decay which have passed since then, there are sufficient remains of Cymer to allow inspection, reflection and even silent prayer.

Aside from a helpful illustrated sign giving a brief overview, there is not much interpretive data at the site today. However, with sufficient wider reading, and the help of Professors Burton and Stober's handy gazetteer, one can piece together the basic set up which would have been established and handed on for centuries at Cymer Abbey.

The gazetteer confirms Colin Platt's theory, itself reliant on a key text called simply (by the alternative spelling) Cymmer Abbey, written in 1946, by C.A. Ralegh Radford, that the church was never completed with its initially projected transepts to make a cruciform plan.

Their gazetteer points out that this also meant that a planned central tower was never implemented. However, it also speaks of an unusual western tower being added in its place.

On the day that we visited, I took this photograph looking skywards through, what I took to be, the remains of that western tower. Certainly, this was present in the western end of the remains of the central church.

Towers were originally heavily restricted in the earliest statutes of the Cistercians, due to the order's theological and mystical desire for simplicity. As the centuries progressed, Cistercian towers did creep in; eventually culminating in the kind of architectural wonder presented, around 1500 AD, by Abbot Huby's magnificent tower at the once-wealthy Fountains Abbey in Yorkshire.

A quick aside to show you Abbot Huby's great tower at Fountains Abbey in Yorkshire. We visited the enormous remains of Fountains in April, 2012; in order to renew our wedding vows at the site of the old High Altar, on our 10th wedding anniversary.

Although Cymer was a poor and small monastic community, the monks still managed to construct a reasonably sized church, with an aisled nave. This next image was taken standing in the northern aisle looking towards the eastern end of the aisle and church.

A neat thing to notice here, is how, in the present day, an arch has been formed in the trees on the valley side above the church, due to a clearing which has been kept to allow electricity lines to come down that side of the valley. As you probably know, this kind of setting in an isolated valley, often close to healthy woodland and river systems, is a classical hallmark of the typical Cistercian monastic settlement.

Colin Platt suggests that, being constructed on a small scale, the choir monks at Cymer would, unusually, have worshipped in the lay brethren's choir.

Moving through the extant medieval arches, we enter the church proper and stand here looking to the east end of the church. Notice the three fine and tall, but simply executed, Lancet windows. Being a poor house, it seems that Cymer did not develop the structure with the kind of splendid tracery which eventually crept into and replaced the simple architecture of the wealthier houses. Â

Other things worth noticing, include, what looks to me to have been the original sanctuary piscina niche, in the south-eastern corner, (to the right of the eastern window wall, but to the left of the arched doorway in the picture), and also some blind arcading to the right of the far doorway.

I always like to try and imagine where the original High Altar would have stood in these ancient monastic sites. Here we have moved in slightly closer towards the sanctuary end of the remains of the ancient church.

After taking this photograph, I moved right on in to where the Altar seemed most likely to have stood. I prayed there in silence for a while. Although there is a working farm next to the site, and a small holiday camp to the other side, there is a pleasant peace at Cymer Abbey anyway. Nevertheless, the peace that came when praying in that east end was intense. It is amazing to think of the Holy Mass and Divine Office being offered, right there by dedicated monks, on so many days, through all those centuries from the foundation in 1198, right through to the Henrician suppression in 1538. That means that a lot of grace came down in that place, and for a very long time. No wonder it remains peaceful to this day to those who stop to pray, listen and sense interiorly in the silence.

Here is a close-up of that blind arcading close to the sanctuary area. It has stood up reasonably well to centuries of the sometimes testing weather in the Snowdonia region. The site is owned and looked after today by Cadw, the Welsh governing body of protected sites.

The remains of this fine archway would originally have linked the church through to the cloister and claustral complex, to the south of the church. On the grass just beyond, the stones marking out the lines of the cloister can be seen. That claustral complex of buildings would have been centred on this cloister and would have included the chapter house, refectory and dormitory. Larger houses eventually built their refectories on a north-south axis, but it seems that Cymer's was in the east-west axis; something that had been typical in many places early in the Cistercian expansion, but had been superseded as the houses of the order gained more members and resources.Â

The standing arches at Cymer are fantastic and it is incredible to think of their historical provenance. In the present day, it is refreshing to stand there and look up to the trees on the surrounding hills.Â

Here is an interesting set of archways; through which one can stand and wonder what might have once been, and indeed what could be again some day.

If you know anything about Cistercian history, you will know that they were experts at land clearance and water management techniques. At Fountains in Yorkshire, one can still see how the monks canalised the River Skell and constructed their kitchens, refectory, dormitory and infirmary in such a way as to make use of the rapidly moving waters for cleaning and drainage. Some Cistercians were also talented makers of ornate taps which fed channelled water into troughs for washing etc.

As with so many things, Cymer's use of water was rather more modest. However, if you look back to the plan near the top of this article, and compare it to the following photograph, it is still possible to see how the original drainage fed straight through under the refectory and reredorter (dormitory).

Here we are to the south of the claustral complex plan looking westwards along the brook. Notice the stones of the old plan of the monastic site crossing the brook. That's our silver wheelchair adapted vehicle in the distance!

You'll also notice the farm house to the right. I've mentioned that Cymer is on the edge of a working farm today. Professors Burton and Stober point out that the extensively restored farm house to the west of the site preserves timber from what was probably an impressive hall. This has been dated to 1441 or soon after by the process of dendro-chronology. As such, the original hall could have been an abbot's lodging, or maybe a guesthouse.

In the early days of the Cistercian reform in the UK, the abbot slept in a niche, or separate room, close to the dormitory. However, as abbeys grew wealthy through land management and agriculture, their abbots became more and more powerful as landowners, and thus increased in temporal status in a way parallel to local feudal lords. To match their heightened status, they constructed ever more ornate lodges at the edge of the monastic sites.

These lodges, which in one or two places had actually reached the grandeur and scale of mansions by the 16th-Century, were used to entertain important guests and benefactors.

Of course, as we have reflected here many times, the monastic world came to an abrupt and cruel end in the 1530's, when King Henry VIII suppressed all of the 800 or so monasteries which were still functioning at that time. Thus bringing to an end a whole empire of prayer, adoration, thanksgiving, intercession; as well as a world of social ordering expressed through the giving of the sacraments, kind acts of charity to pilgrims and travellers, care of the sick and dying, provision of food and supplies to the poor, offering of education, provision of security for deeds, documents and money, and management of land, water and commerical interests.

It is interesting to notice how the attack on the monasteries, and the essential monastic prayer that issued from them, came from without in the 16th-Century.

In our day, after almost five further centuries of associated religio-cultural deformation, the attack on the always-vital monastic life is now coming from within.

I've said before that, although it is possible to overstate the case, there really was once a merry olde medieval world, which developed as the fruit of a genuinely Catholic Christendom.

Having already and rhetorically asked here before, whether the UK was ever so merry again after our nation lost the Catholic Faith, let us conclude with some moving words from the end of Colin Platt's engaging book, The Abbeys and Priories of Medieval England. Whilst including quotes with the spelling from old English, it also gives food for thought in terms of the present-day depredations which have been described above; depredations which need to be resisted.

''In the meantime, though, a sense of desolation had developed. Shakespeare writes of those 'bare, ruined choirs where late the sweet birds sang'; Donne of the winds which 'in our ruin'd Abbayes rore'. In humbler but no less poignant vein, Francis Trigge would report in 1589: 'Many do lament the pulling downe of abbayes. They say it was never merie world since.'''

Well, I say we need to make the Church and the world merry once again: Stand up for the true nature of religious life and defend the holy nuns, monks and consecrated virgins who live the religious life, as the very heartbeats at the centre of the Church's life. May we not fail them, as did our forefathers in the 16th Century.

St. Mary, Patroness of Cymer - Pray for us!